Abstract

This paper formalizes a common approach for estimating effects of treatment at a specific location using geocoded microdata. This estimator compares units immediately next to treatment (an inner-ring) to units just slightly further away (an outer-ring). I introduce intuitive assumptions needed to identify the average treatment effect among the affected units and illustrates pitfalls that occur when these assumptions fail. Since one of these assumptions requires knowledge of exactly how far treatment effects are experienced, I propose a new method that relaxes this assumption and allows for nonparametric estimation using partitioning-based least squares developed in Cattaneo et. al. (2019). Since treatment effects typically decay/change over distance, this estimator improves analysis by estimating a treatment effect curve as a function of distance from treatment. This is contrast to the traditional method which, at best, identifies the average effect of treatment. To illustrate the advantages of this method, I show that Linden and Rockoff (2008) under estimate the effects of increased crime risk on home values closest to the treatment and overestimate how far the effects extend by selecting a treatment ring that is too wide.

5-Minute Summary

The rise of geocoded microdata has allowed researchers to begin answering questions about the effects of spatially-targeted treatments at a very granular level. How do local pollutants affect child health? Does living within walking distance to a new bus stop improve labor market outcomes? How far do neighborhood shocks, such as foreclosures or new construction spread? A standard method of evaluating the effects of the treatment is to compare changes in outcomes for units that are close to treatment to those slightly further away – what I label the ring method.

The motivation for such a design is that since both the ‘treated’ and the ‘control’ units are within. the same local neighborhood, they should be subject to common shocks. For example, Asquith et al. (2021) write “The idea is that within a small area, developers have few sites that are available and properly zoned, leading to hyper-local variation in the location of new construction that is not related to future price changes.” I show in this paper that the currently proposed method does not fully use this common shocks assumption and in turn (i) estimate results that are biased except under a very strong assumption and (ii) estimate an ‘average effect’ instead of the full treatment effect curve.

Problems with the standard ring method

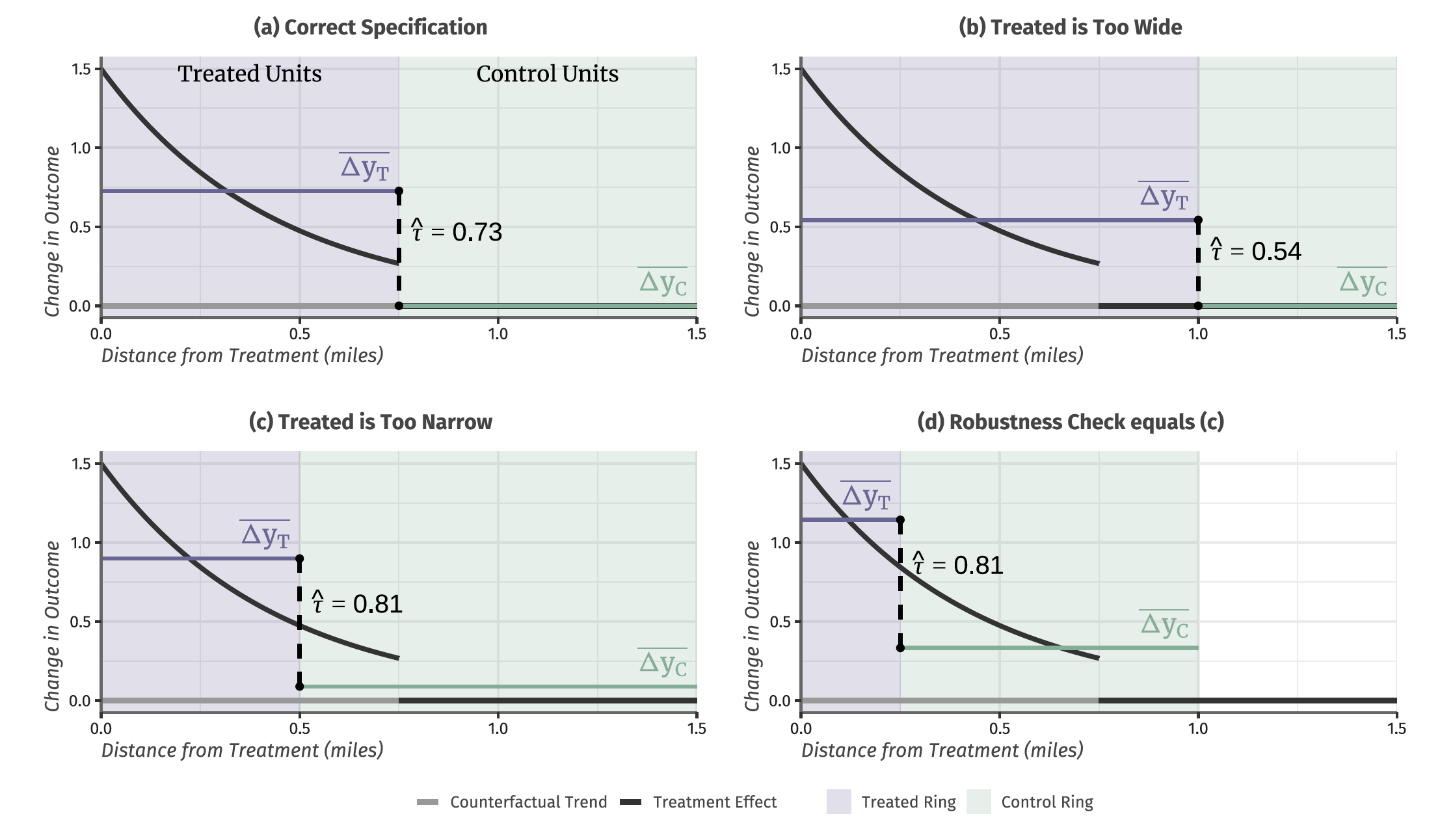

First, the problems with the standard ring method. In the below figure, I show 4 different “estimates” using the ring method for the same data-generating process. The black line highlights the treatment effect curve which declines over distance and becomes zero after 0.75 miles. The gray line shows the counterfactual shock, which under the common shocks is constant across distance and normalized to zero. For each estimate, the researcher compares the average change in outcomes in the treated section to the average change in outcomes in the control section, a difference-in-differences estimator.

The top left panel, shows the ‘oracle’ estimator where the researcher knows how far treatment effects travel (this is a very hard thing to justify and is usually an ad-hoc choice). In this case, the researcher is able to correctly identify the average treatment effect among the affected. Note, however, that this estimate masks over interesting heterogeneity in treatment effects over distance, with the closest units experiencing twice as large of a treatment effect as the average. Later on, I propose an estimator that estimates the average treatment effect as a function of distance.

It is not common, though, to know how far treatment effects travel. Hence, researchers typically will select the wrong distance. The problems arise are shown in the top-right and bottom-left panels. The top-right panel shows when the treatment ring is too wide. Since units experiencing no treatment effects are included in this sample, the average treatment effect is attenuated towards zero. The bottom-left panel shows when the the treatment ring is too narrow. In this case, the counterfactual trend estimated by the control unit is biased and hence the average effect is biased as well.

Researchers have recognized this problem and have proposed selecting alternate rings as ‘robutsness checks’. The bottom-right panel shows the problem with this strategy. Consider using the bottom-left panel as your main specification and the bottom-right panel as your ‘robustness check’. In both cases, you find the same treatment effect and neither of them are correct.

Non-parametric Rings Estimator

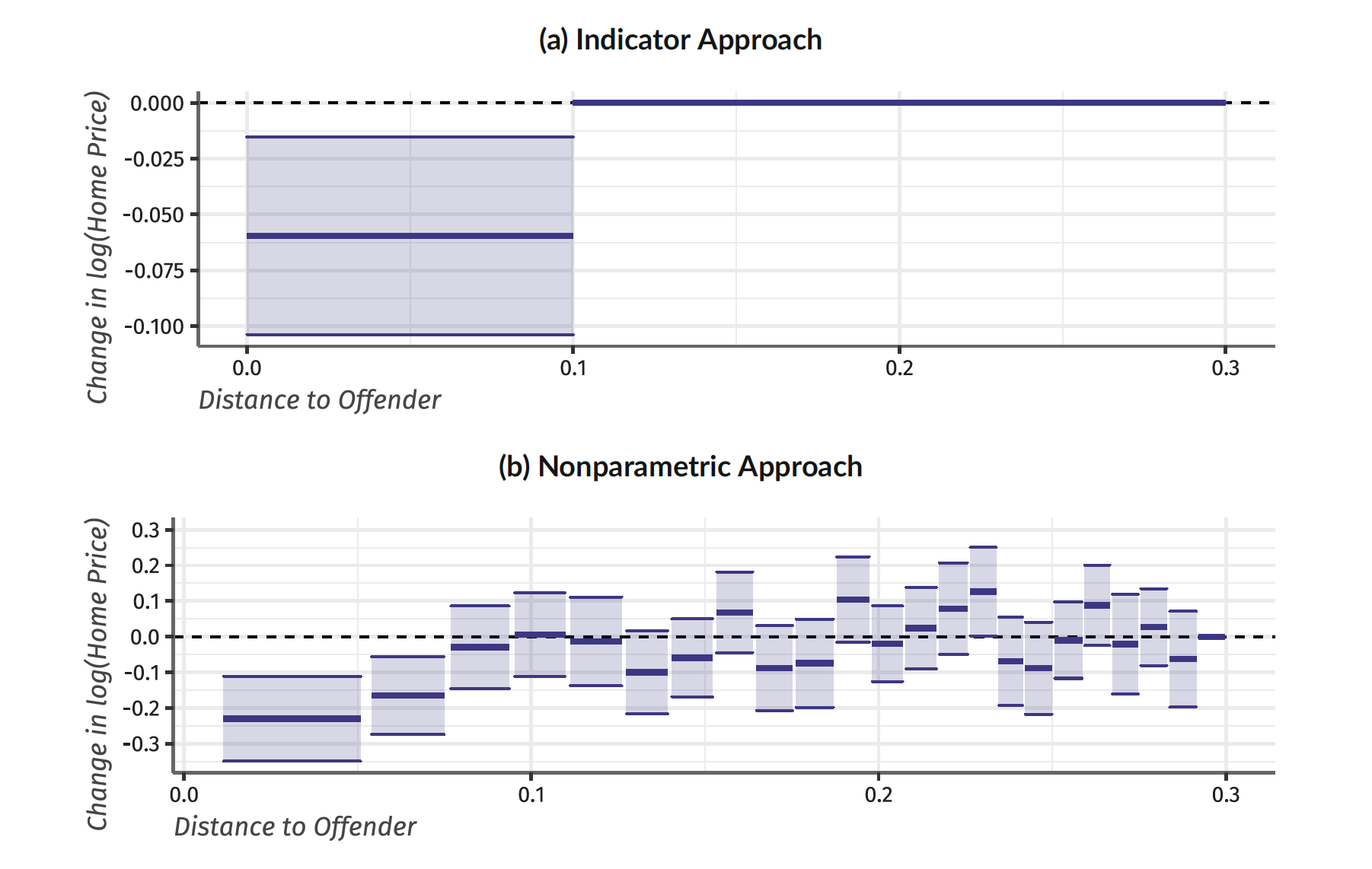

The central idea behind my proposed estimator is instead of having a single treatment ring and a single control ring to have many rings. The furthest away ring will estimate the common shock while the other rings will each estimate the treatment effect for that distance from treatment. For example, see the below figure which recreates the results of Linden and Rockoff (2008) who study the effects of a sexual offender arriving to your neighborhood on home prices. The top panel is the standard rings estimator. Notice they choose a cutoff and then assume the treatment effect is constant within the treated ring and that after their cutoff the effects are zero.

In contrast, the bottom panel performs the non-parametric rings estimator I propose in my paper. The figure more clearly shows that there are very large effects very close to the sexual offender’s home and they decay to zero and then “treatment effect” estimates are centered at zero after 0.1 miles. The results of my method (i) provide more interesting information on heterogeneous treatment effects while (ii) not requiring the correct specification of the treatment effect distance.

In my paper, I dive into the non-parametric method as originally proposed in Cattaneo et. al. (2019) and prove my identification results, but there is one more important advantage to note in my estimator. The number and location of the rings is decided in a completely data-driven and optimal manner removing potential researcher degrees of freedom. Since the choice of treatment and control rings is typically done in an ad-hoc manner, my proposed estimator provides robustness against accidentally choosing rings that produce large results or rings that produce near-zero results.