Abstract

The U.S. federal government awards billions of dollars of contracts annually to private-sector firms to produce a wide range of goods and services. However, little is known about how a reduction in federal procurement, also referred to as fiscal consolidation, impacts local labor markets. In this paper, we leverage the institutional details of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) and highly detailed transaction-level data for procurement by all federal agencies to estimate the effect of fiscal consolidation on local employment and wages. Our identification strategy uses a shift-share instrument and is based on the exogeneity of the BCA-induced spending cuts across industries, i.e. exogenous shocks. Our results show that the local effects of consolidation depend on the factor intensity of the sectors receiving federal dollars. We find that a $1 million reduction in federal contract spending reduces employment by more than 12 jobs in high labor-intensive industries (factor intensity of over 45% of production) and only around seven jobs in low labor-intensive industries (factor intensity of less than 15%). We also find that, relative to wages, employment appears to be the key margin for local labor market adjustment in the wake of consolidation. These findings suggest that nominal wage rigidity is an important mechanism in negative demand shocks.

5-Minute Summary

A nascent literature in the field of urban economics and macroeconomics has aimed to understand the local impacts to federal spending, estimating “fiscal multipliers”. However, this literature has only considered periods of fiscal expansion when government spending increases. There are theoretical reasons to suspect that firms will respond differently to increases and decreases in government spending. In periods of expansion, existing results suggest that firms raise wages or increase hours to meet the increasing demand. However, when firms face negative demand shocks it is difficult to lower wages, a theory called “nominal wage rigidity”. Instead, firms would primarily have to rely on the extensive margin of employment to adjust to negative demand shocks.

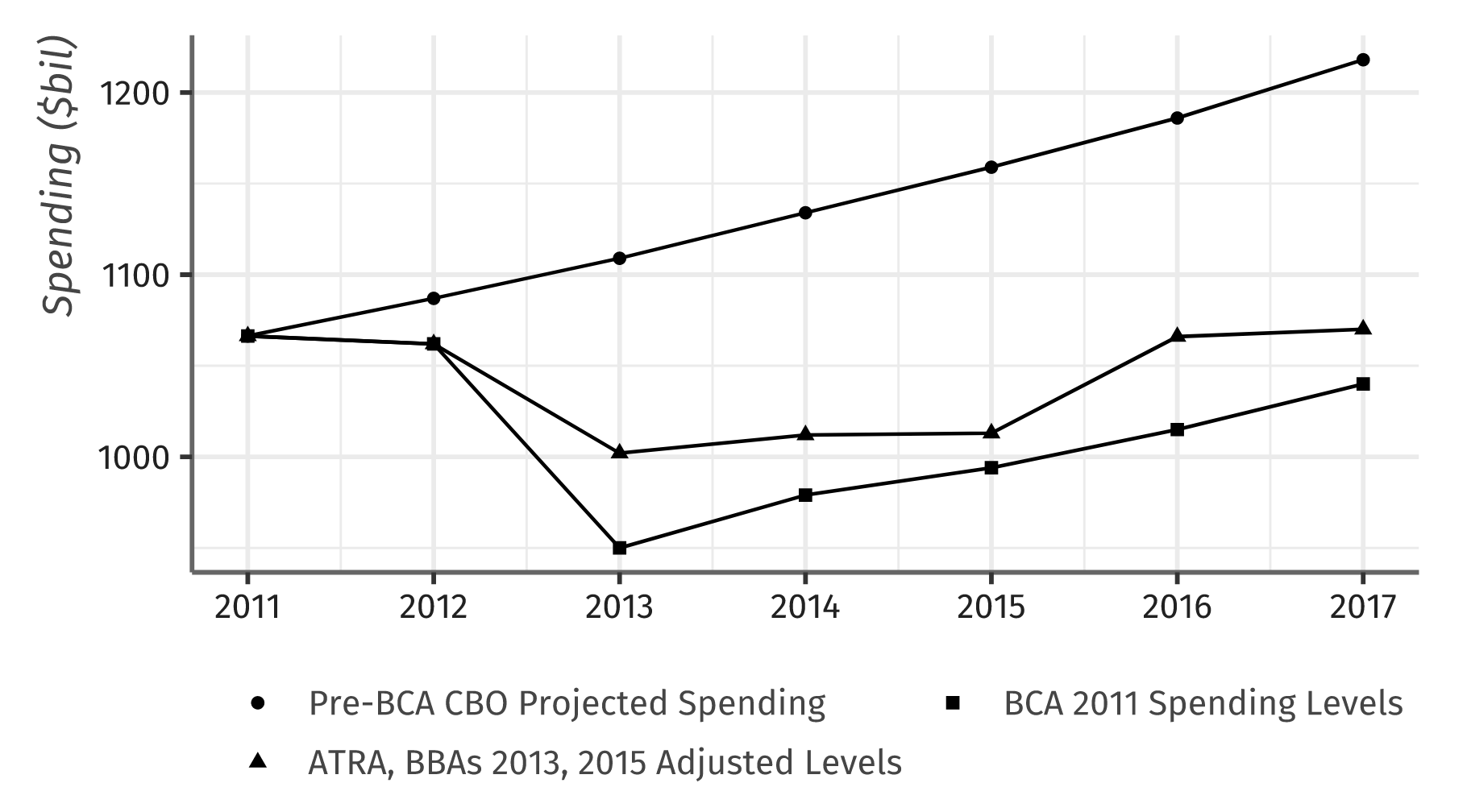

This paper analyzes a period of fiscal consolidation induced by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA). The below figure shows the BCA-induced federal spending cut was large (predicted cuts over around 1000 billion dollars). All government agencies (and subagencies) were required to cut spending by a given percent and were given discretion over where to make these cuts. In sum, we argue that the aggregate shocks (summed over agencies/subagencies) is exogenous to local labor markets.

Our paper uses a shift-share style instrument to leverage these exogenous shocks to procurement spending in CBSAs across the US. We predict spending for CBSA in fiscal year by taking a measure of per-capita spending in

2010 (pre-BCA) and multiplying it by a CBSA’s exposure to national spending shocks. Our instrument for predicted spending is given by

where is the 2010 share of employment in CBSA in industry and is the national change in procurement spending for industry . In the paper we check two ways this instrument could be invalid, following suggestions from Borusyak et. al. (2022). First, we could be concerned that the aggregate spending shock is correlated local employment. We show that a CBSA’s predicted spending shock is uncorrelated with lagged changes in employment and wages (a pre-trends test). Second, we could be concerned that spending shocks were targeted to places without much political power. This does not show up in the data for four different proxy variables for political power.

The paper goes into much more exciting econometric details on shift-share instruments and gives more institutional details to support our instrument.

Results

Our main results show that in response to a 1 million dollar decrease in procurment spending, 10.5 jobs are destroyed. The employment effect we estimate is considerably large than Auberbach et. al. (2020) and Gerritse and Rodríguez-Pose who estimate 8 and 4 jobs, respectively, are created when increasing procurement spending by 1 million dollars. On the other hand, the wage effects we find in periods of fiscal consolidation are smaller than the wage adjustments the other papers have found. Together, we find that firms respond more strongly on the employment margin when faced with negative demand shocks relative to positive ones.

As discussed above, one theory to explain this is the theory of nominal wage rigidity in which firms are not able to adjust adjust wages down and so they are only able to adjust on the employment margin. To test more formally test this theory, we use KLEMS data estimates of labor shares of production in different industries. Therefore, we are able to test how fiscal multipliers change for firms with more or less labor factor intensity in their production function. We find that for firms with 0-15% labor shares, a decrease in spending of 1 million dollar destroys 7.5 jobs while 12.25 jobs are destroyed for firms at the top quartile of the distribution, with labor shares of over 45%. We don’t find significantly different effects on wages, providing evidence in support of the nominal wage rigidity theory.